Ferlov Mancoba

Ernest Mancoba - Selected sources

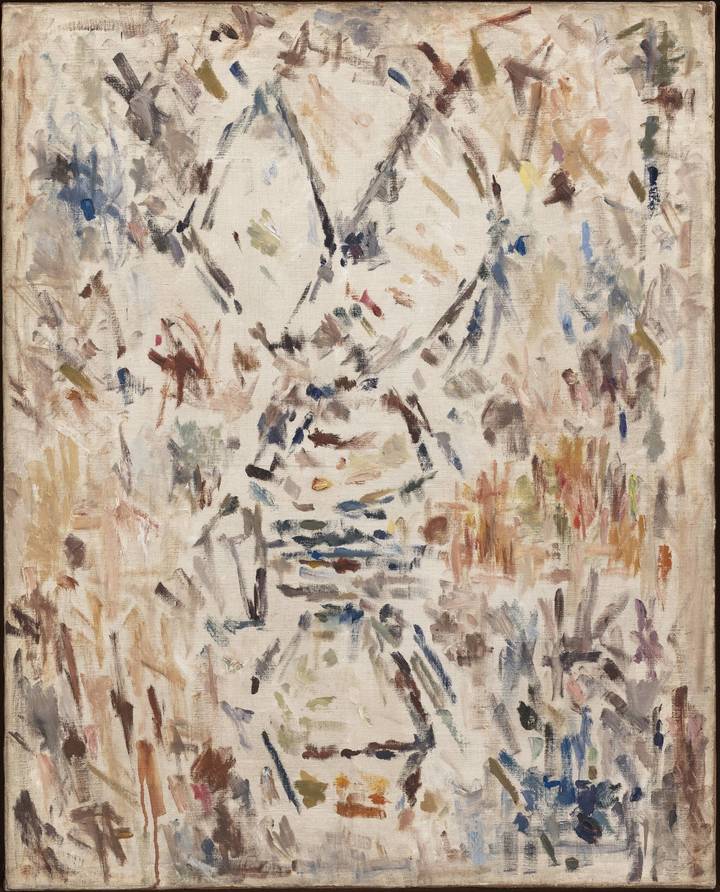

Ernest Mancoba

Untitled. 1965

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

The database for Ernest Mancoba (1904-2002) contains digitized items drawn from the Ferlov Mancoba archive. The archive is owned by the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba and housed at the SMK - National Gallery of Art, Denmark in Copenhagen. The archive consists of the archival materials left by the artist family of Sonja Ferlov Mancoba (1911-1984), Ernest Mancoba and Marc (Wonga) Mancoba (1946-2015) and includes letters, printed materials, books, photographs, and various items. The database for Sonja Ferlov Mancoba is also drawn from the Ferlov Mancoba archive. The two artists were married, and their art, networks, and lives were closely intertwined for most of their lives and many sources of knowledge about them are common to both. For instance, it was Sonja Ferlov Mancoba who wrote and received letters on behalf of the entire family, and often, the letters concerned both artists.

The archive was compiled during the last years of their son Marc, known as Wonga, Mancoba and had been stored at Rue du Château 153, Paris, where the family lived and worked from 1961 onwards. Most of the materials date from this period with fewer archival materials from 1938-1960, presumably due to the family's turbulent life in Denmark and France. Fortunately, several of Ernest Mancoba’s early diaries have been preserved.

The database consists of identity documents, a selection of letters, diaries, manuscripts and audio files. The archive materials in the database reveal Mancoba’s background and ties to South Africa, France and Denmark. Through letters, diaries, manuscripts, and audio files we can trace a chronology of his life and how he engaged with art and society.

In our selection of sources from the Ferlov Mancoba archive we have focused on making the diaries and audio recordings by Ernest Mancoba accessible. In the case of the audio recordings of interviews of Mancoba by Wonga, we decided against transcriptions as they cannot capture tonal cues. Instead, time indices are provided, and these are based on the archivist’s interpretation of the conversation.

The database also presents several identity documents, to aid research with regards to dates of travel, internment periods etc. Note the veracity of the identity documents corresponds with the times. For example, the passports note Mancoba’s birth year as 1907 whereas he has said that it was 1904. There is no known birth certificate.

In the selection of letters, focus is on correspondence to and from Ernest Mancoba and Sonja Ferlov Mancoba and their relations in South Africa, Denmark and France. We have prioritized transcription of handwritten letters in Danish to make them more accessible to a broader readership. With regards to annotation of the sources we have focused on South African and Danish aspects to aid a broader readership.

The selection and annotation of the database reflects our individual scholarly profiles, both our strength and our blind spots. The aim is to present the material as openly and transparently as possible for scholarly and general readership. We hope the database will be useful for readers worldwide.

Ernest Methuen Mancoba was a South African-French visual artist with close ties to Denmark. He was born and raised in South Africa but lived in France and Denmark from 1938 until his death in 2002. Mancoba is a central figure in global modernism, and worked with painting, drawing, and wooden sculpture and printmaking. He is best known for his modern, spontaneous abstract style, with an embedded central figure – which has been said to reference an African ancestral figure. Ernest Mancoba has been described as South Africa’s first modern artist. His art emerges from the meeting between South African culture and modern European visual art.

Mancoba identified himself in his art and spirituality with the African Ubuntu philosophy’s credo that a person is a person through other persons. He believed that art could build bridges between people, and that it was only through other people that we exist. Through this, our humanity, our humanism, arises. He formulated a unique aesthetic connected to a personal spirituality. At the same time, he was also a part of the artists’ groups “Høst” and “Cobra” that sought a kind of re-enchantment of their modern world.

Mancoba worked with wood sculpture in South Africa. In 1938, Mancoba sailed via London to Paris and studied at L'École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. There, he met the Danish ceramicist Christian Poulsen (1911-1991), who introduced him to a circle of young Surrealist-oriented Danish artists who were also in Paris, including Ejler Bille (1910-2004) and Sonja Ferlov.

During World War II, from 1940-1944, Mancoba was interned in various prisons and concentration camps in Paris and the surrounding area: Fresnes, Drancy, and La Grande Caserne at St. Denis, due to his British citizenship as a South African. Ernest Mancoba and Sonja Ferlov married in 1942 in St Denis camp. The camp allowed some correspondence and Mancoba was able to keep a secret diary. In 1947, the Mancoba couple moved to Denmark; through artist friends like Asger Jorn (1914-1973) and Bille, Mancoba exhibited with the Høst (Harvest) artist association in 1948 and 1949, and he and Ferlov Mancoba became involved with the Cobra movement. In Denmark, Mancoba continued work with wooden sculptures, which had become column-like and totemic. He also turned to painting, his use of color and brushwork inspired by African visual traditions and the fresco paintings in Danish medieval churches.

In 1952, the Mancoba family moved back to France, first to the village of Oigny-en-Valois and in 1961 to Paris, where they lived for the rest of their lives and obtained French citizenship. During this period and beyond, Mancoba concerned himself with painting and drawing, and in later years, printmaking. The paintings were abstract but revolved around a figure. Art historians have pointed to various sources of inspiration, including Central and West African peoples’ funereal figures. However, Mancoba worked with multiple sources of inspiration and freely engaged with his references. After the death of his wife Sonja Ferlov Mancoba in 1984, there was a shift in Mancoba’s art, moving away from the solitary figure towards works where multiple figures or calligraphic brushstrokes spread across the entire surface.

Karen Westphal Eriksen and Winnie Sze, February 2025